Like many other food allergic children, my childhood consisted of countless doctor visits and a constant fear for my life. I was severely allergic to dairy, wheat, egg, peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish, and well, you get the point. I was allergic to what felt like everything, which had a tremendous impact on my life and the lives of those around me. I am like many whose childhoods were tainted by the disease, yet I am unlike them in that I had the opportunity to overcome my allergies through oral immunotherapy (OIT) — a treatment that saved my life, gave me a new life, and continues to do so through my advocacy work and advisor role at Latitude Food Allergy Care.

Before I was two years old, a glass of cow’s milk spilled on my hands, sending me into anaphylactic shock. From then on, my family led a life of diligent avoidance; however, this did not prevent further near-death episodes. In first grade, a piece of toast — a brand I had trusted in the past — caused my throat to swell. I remember being at my allergist’s office, paramedics surrounding me, and my mom trying to keep me awake as my eyes drifted shut.

The following year, my family finally gained the courage to eat at a restaurant. My mom spent weeks vetting the place, interrogating the chefs, and analyzing every label in the kitchen. The day when we were finally ready to eat there, the kitchen ran out of rice noodles, switching to wheat noodles without telling us. On the way home, I told my mom “I feel funny,” which was the only way that I knew how to tell her that I was potentially losing my airway and needed epinephrine.

After the cumulative effects of all of my reactions, the bullying that I experienced at school, and my inability to participate in the normal aspects of life, my final straw came one day after diving practice. My mom had just begun to leave me alone at the pool, and she bought me a flip phone to stay in touch with her. On this day, she stayed behind to have a conversation with one of my coaches. Normally, this would have been an annoyance, but her unrelenting desire to communicate with everyone she sees saved my life that day. About 15 minutes into my exercise, I started to “feel funny.” I told my mom, we called an ambulance while using two rounds of epi, and another parent — a nurse — encouraged me to pump my albuterol inhaler as if it was oxygen. The paramedics asked if it was hard to “breathe in” or “hard to breathe out.” I remember being so confused by this question, feeling like I couldn’t do either. On the ambulance ride to Stanford Hospital, hearing my mom frantically try to contact my father behind me so he could pick up my sisters that we had to leave behind with another parent, I thought to myself “my greatest fear came true.” I always had an irrational fear of having a reaction in a wet swimsuit! Again, after all of the trauma that I had experienced at the hands of my allergies, the universe dealt me a final, divisive hand, that almost broke me.

During every waking hour between each one of these experiences, my mom searched for a solution. We’d been told to just avoid my allergens and that there was no other option. But, we had learned that even the most obsessive avoidance, calculating every bite, inspecting every room, and evaluating every relationship, could still lead to danger. After slews of skin tests, blood draws, and travels across the country in search of a cure, my mom finally found an answer. She went to hear a speech given by Dr. Kari Nadeau at Stanford who was conducting primitive clinical trials to treat milk and peanut allergies. My mom went up to her afterwards and asked if there was anything to be done for children like me with multiple allergens. Dr. Nadeau said “I don’t know but I promise I will figure it out.” Thus began what has turned into more than a ten year relationship between my mom and Dr. Nadeau. My mom worked tirelessly leading up to and beyond my treatment to raise funds for what would become the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford University. She spent years fundraising and helping families receive the treatment that they universally yearned for. Both Dr. Nadeau and my mother are inspirations. My mom especially prevailed against all odds, working passionately not only to provide a safe future for her own daughter, but for the rest of the world too.

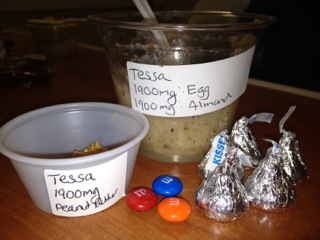

I began “double blind food challenges” for the clinical trial during the summer of 2011, when I was nine. I started to take Xolair (omalizumab) in December and two months later began taking my first “doses.” I ate powdered protein of milk, wheat, egg, peanut, and almond (we could not treat all of my allergens but chose my five most severe allergens). Doses began as essentially grains of sand and I would go to the hospital every two weeks to “updose” and increase the amount of protein that I could tolerate. After each visit, I went home with a new set of measured proteins, which I would eat in applesauce, smoothies, and Pillsbury icing in moments of weakness. Oral immunotherapy desensitizes you to your allergens by slowly increasing a miniscule dose until you can tolerate the desired amount. By May of 2012, I was eating cupcakes and pizza and a celebratory cake to commemorate my graduation from the trial. I was the first person to be treated for multiple food allergies, and my life changed forever. Although the months during treatment were difficult, the prospect of at least some relief kept me going.

Having gone through this landmark clinical trial, I was grateful to receive the opportunity to share my story with others — as living proof and a sign of hope for families who continued to struggle. My story was covered by Melanie Thernstrom at the New York Times, who wrote a cover-story for the magazine in March 2013. I appeared on the Today Show, Katie Couric, and local news outlets to share my story. After I was treated and I could live more normally, I wanted to ensure everyone like me could have the same access.

After an incredible response to our message of hope and my mom’s years of experience working with other food-allergic families from across the country, my mom was inspired to create a tangible way to provide food allergy care to all the families in need. Long story short, she founded Latitude Food Allergy Care to provide the care for food allergic families that we so desperately needed when I was younger.

I have been involved in Latitude’s creation from the inkling of an idea, helping out as a patient advocate, summer intern, and curious teenager fly on the wall. From picking fabrics for the flagship clinic (no carpet — I once had a reaction from a Goldfish cracker stuck in carpet!) to staffing the company’s booth at the 2019 FARE Contains Courage Convention, I have been invested. Aside from my work at Latitude, I have also continued advocacy for food allergic families at the Food and Drug Administration (testifying on behalf of the first drug for food allergy), at insurance review board meetings, and at FARE’s convention. Any opportunity to share my story and show others that I survived food allergies, underwent treatment, and emerged thriving, is one I am thrilled to take.

There is so much hope for food allergic families today. I see it whenever I visit Latitude’s bustling clinic or even when I go out for ice cream. There are solutions, options, REAL LIFE FIXES for food allergies, and they are becoming increasingly accessible. Pretty soon, no child will endure the burdens and traumas of food allergies.